The human brain wasn’t designed for the modern workplace. While we’ve evolved sophisticated cognitive abilities over millennia, our neural architecture remains fundamentally single-threaded. Yet we live in an age that demands constant multitasking, context switching, and divided attention. The result isn’t just decreased productivity—it’s a systematic rewiring of our cognitive capabilities that may be permanently altering how we think, focus, and create.

Recent neuroscience research reveals that what we call “multitasking” is actually rapid task switching, and each switch carries a hidden cognitive cost that compounds throughout the day. Understanding this mental overhead and learning to manage it effectively might be the single most important productivity skill for the modern knowledge worker.

The Neuroscience of Context Switching

When you shift from reading emails to writing code to attending a meeting, your brain doesn’t instantly flip between modes. Instead, it undergoes a complex neurological process called “task switching cost.” Brain imaging studies show that switching between tasks activates the prefrontal cortex—the brain’s executive control center—which must work overtime to inhibit the previous task while orienting toward the new one.

Dr. Daniel Levitin’s research at McGill University found that this switching process burns glucose, the brain’s fuel source, faster than focused attention. The result is mental fatigue that accumulates exponentially rather than linearly. After just two hours of frequent task switching, participants in his studies showed decreased IQ scores equivalent to losing a full night’s sleep.

The implications become stark when you consider the modern workplace. Knowledge workers check email every 6 minutes on average and are interrupted every 11 minutes. Each interruption triggers this costly switching process, creating a state of continuous cognitive drain that most people mistake for normal mental fatigue.

The Attention Residue Phenomenon

Beyond immediate switching costs, researcher Sophie Leroy discovered that fragments of our attention remain stuck on previous tasks—a phenomenon she termed “attention residue.” When you finish a complex analysis and immediately jump into a brainstorming session, part of your cognitive capacity remains occupied with analytical thinking patterns, reducing your creative problem-solving abilities.

This residue effect explains why many professionals feel mentally scattered despite staying busy all day. Their attention never fully commits to any single task, creating a perpetual state of cognitive fragmentation. The solution isn’t working harder—it’s working with cleaner mental transitions.

Leroy’s research suggests that completing tasks fully before switching reduces attention residue significantly. However, in practice, most knowledge work involves ongoing projects that can’t be “completed” in single sessions. This creates a productivity paradox where the nature of complex work conflicts with optimal cognitive functioning.

The Myth of Efficient Interruption

Technology companies have built entire ecosystems around the myth that interruptions can be made efficient through better tools and notification management. Slack promises to reduce email overload but often increases interruption frequency. Project management tools aim to provide clarity but create new streams of status updates and notifications.

The fundamental flaw in this approach is treating interruptions as an information architecture problem rather than a cognitive one. No matter how elegant the interface or how relevant the notification, each interruption still triggers the same neurological switching costs. A “quick” Slack message might feel less disruptive than a phone call, but both require the same expensive cognitive gear-shifting.

Research by Dr. Gloria Mark at UC Irvine found that it takes an average of 23 minutes and 15 seconds to fully refocus after an interruption. Yet most knowledge workers experience interruptions far more frequently than every 23 minutes, meaning they never actually achieve full focus during their workday. They operate in a constant state of partial attention, never experiencing the deep cognitive states where their best work happens.

The Deep Work Deficit

Cal Newport’s research on “deep work”—the ability to focus without distraction on cognitively demanding tasks—reveals that this skill is becoming increasingly rare precisely when it’s becoming increasingly valuable. The ability to quickly produce high-quality work depends on sustained attention, but modern work environments systematically prevent this sustained focus.

The scarcity creates a competitive advantage for those who can cultivate deep work abilities. Newport’s data shows that knowledge workers who protect large blocks of focused time consistently outperform their more “available” colleagues, often producing significantly more valuable output in fewer total hours.

However, cultivating deep work requires more than individual discipline. It requires restructuring how teams communicate, how meetings are scheduled, and how urgent versus important work is prioritized. Most productivity advice focuses on personal optimization while ignoring the systemic forces that fragment attention.

The Pomodoro Principle and Its Limitations

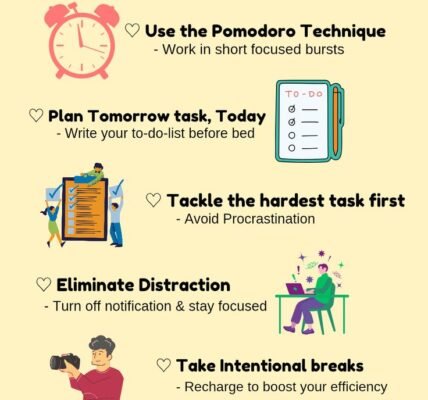

The Pomodoro Technique, which involves working in 25-minute focused intervals followed by short breaks, gained popularity partly because it aligns with natural attention rhythms. However, research suggests that 25 minutes is often insufficient for entering flow states, particularly for complex cognitive tasks.

Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s flow research indicates that entering deep focus typically requires 15-20 minutes of sustained attention before the brain shifts into optimal performance mode. A 25-minute Pomodoro allows for only 5-10 minutes of actual deep work before the break interrupts the flow state.

More effective approaches involve longer focused blocks—90 to 120 minutes—followed by substantial breaks. This aligns better with natural ultradian rhythms, the 90-minute cycles that govern alertness and attention throughout the day. However, implementing longer focus blocks requires more significant changes to work structure and environment.

The Communication Paradox

Modern knowledge work creates a paradox: collaboration requires communication, but communication destroys the sustained attention that produces the best collaborative work. Email, instant messaging, and video calls enable coordination but prevent the deep thinking that creates value worth coordinating around.

Some organizations are experimenting with “communication batching”—designated times for messages and meetings separated by protected focus periods. Buffer, the social media company, implements “No Meeting Wednesdays” to provide at least one day per week of uninterrupted work time. Their productivity metrics show significantly higher output on these protected days.

However, batching communication requires organizational discipline that conflicts with cultural expectations of immediate responsiveness. Clients, managers, and colleagues often interpret delayed responses as lack of commitment rather than focus optimization. Changing these expectations requires explicit communication about focus management practices.

Environmental Design for Sustained Attention

The physical and digital environment plays a crucial role in supporting or undermining sustained attention. Open offices, despite being designed for collaboration, consistently reduce deep work quality due to visual distractions and noise pollution. Research by Harvard Business School found that open offices actually decrease face-to-face communication by 70% while increasing digital communication, creating the worst of both worlds.

Digital environments present similar challenges. The average knowledge worker has 9.6 browser tabs open simultaneously, with email and messaging applications running continuously in the background. Each visible notification or interface element consumes cognitive resources through what researchers call “cognitive switching costs.”

Creating environments that support sustained attention requires intentional design choices: physical spaces that minimize visual distractions, digital tools that batch rather than stream information, and social norms that respect focused work time. These environmental factors often matter more than individual willpower or time management techniques.

The Creativity Connection

The relationship between attention management and creativity reveals why task switching is particularly damaging for innovation-dependent roles. Creative insights often emerge from the intersection of sustained focus and mind-wandering, a cognitive state that requires unstructured mental space.

Research by Dr. Mary Helen Immordino-Yang at USC shows that creative breakthroughs typically occur during “default mode network” activation—periods when the brain isn’t focused on specific tasks. However, achieving this state requires first exhausting active problem-solving attempts through sustained focus, followed by genuine mental downtime.

Constant task switching prevents both the sustained focus needed to fully engage with creative problems and the mental downtime needed for breakthrough insights. The result is a cognitive state optimized for routine task completion but poorly suited for innovation or original thinking.

Practical Implementation Strategies

Transitioning from task-switching to sustained attention requires systematic changes rather than willpower alone. Effective strategies address both individual habits and environmental factors:

Time Blocking with Buffer Zones: Instead of scheduling back-to-back meetings, build 15-minute buffers between activities to allow for mental transitions. Use these transition periods for light tasks like email processing rather than demanding cognitive work.

Attention Anchoring: Begin each focused work session with a consistent ritual—reviewing objectives, clearing the workspace, or doing brief breathing exercises. These anchors help the brain transition more quickly into focused states.

Communication Protocols: Establish explicit agreements with colleagues about response times and availability. Use status indicators to signal focus periods and batch non-urgent communication into designated windows.

Environmental Optimization: Create physical and digital workspaces that support sustained attention. This might involve noise-canceling headphones, website blockers, or dedicated devices for focused work.

The goal isn’t eliminating all interruptions or communication—it’s creating intentional boundaries that allow for both collaboration and deep work. The most productive professionals aren’t those who work the most hours, but those who protect their cognitive resources and deploy them strategically on their most valuable work.

Understanding the hidden costs of task switching transforms productivity from a time management challenge into a cognitive resource management challenge. The question isn’t how to fit more tasks into your day—it’s how to structure your day so your brain can perform at its highest level on the work that matters most.